A Case Study of Ambassador Irit Ben-Abba (2021–2025)

By: Dr. Yang Meng

Israel’s diplomatic predicament vis-à-vis China cannot be understood without first examining the profound transformation of China’s discourse on Jews and Israel over the past three decades. The shift has been neither linear nor accidental; it has unfolded through three distinct phases that fundamentally reshaped the environment Israel must navigate today.

The first phase began in 1992, with the establishment of diplomatic relations. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, China’s mainstream discourse was overwhelmingly positive. Narratives centered on Jewish intelligence, diligence, commercial success, and the Shanghai refuge story, producing an imagery of admiration and cultural affinity.

Around 2010, the rise of social media introduced a fragmenting phase. The previously coherent positive imagery gave way to competing interpretations. Nationalist readings of Israeli geopolitics gained visibility; conspiracy theories imported from the West entered Chinese digital spaces; and real-time exposure to Middle East conflicts recast Israel as a geopolitical actor rather than a historical victim.

The third phase emerged in the 2020s, when these fragmented narratives consolidated into a more polarized and increasingly hostile environment. Antisemitic tropes and anti-Israel narratives circulated widely, amplified by algorithms and the intensifying U.S.–China rivalry. At the same time, the institutional infrastructure that once supported Sino–Israeli academic, cultural, and educational exchange had largely collapsed, leaving very few mechanisms through which Israel could meaningfully engage Chinese society.

These three turning points correspond directly to Israel’s current structural constraints in China: the once-open political environment has narrowed under geopolitical US-China rivalry; China’s perception of Israel has shifted from admiration to suspicion and hostility; and the collapse of academic and cultural exchanges has deprived Israeli diplomats of the networks required for effective public diplomacy. It is within this transformed landscape that the term of Ambassador Irit Ben-Abba (2021–2025) must be understood. Her term did not create these challenges; it unfolded inside them. And the difficulties she encountered reflect not only personal missteps, but also deeper institutional weaknesses in Israel’s diplomatic system, which became far more visible after October 7.

The first major issue that emerged during her term was the her failure to respond to early warnings about the rising antisemitism on Chinese social media. Well before October 7, both Chinese and Israeli scholars alerted the Ambassador to escalating hostility on Chinese social media platforms such as Weibo, Douyin (Chinese Tiktok), and Bilibili. Yet little action followed. Instead, in May 2023, the embassy mistakenly boycotted a lecture by Professor Yin Gang, one of China’s most consistent advocates of China–Israel relations. Although the Ambassador later apologized, the incident significantly undermined trust.

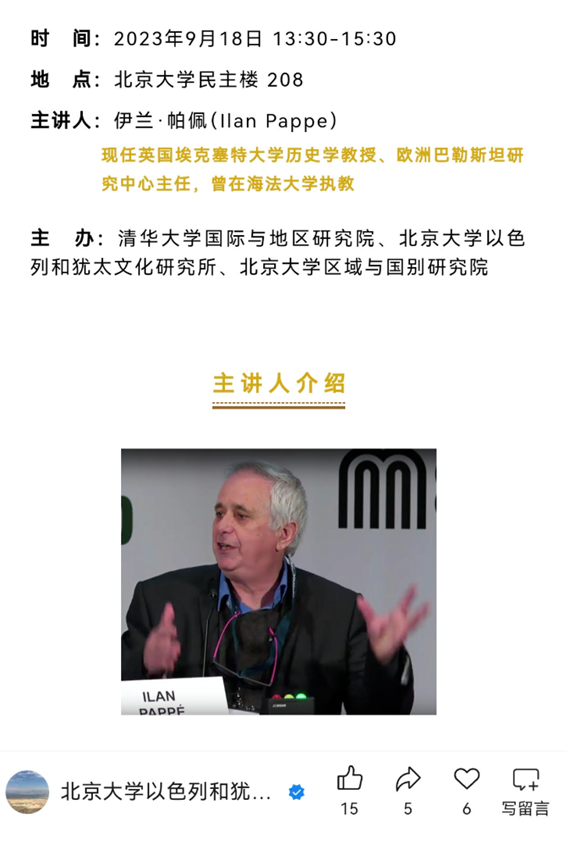

This inversion was even more damaging than it first appeared: the embassy openly boycotted one of Israel’s strongest supporters, remained silent when post-Zionist figures like Ilan Pappé were given platforms at major Chinese universities, an most troublingly, said nothing about Chinese academics whom it knew were actively promoting antisemitic narratives on campus and on social media. For the few Chinese scholars who had long defended Israel in good faith, this sequence of decisions was profoundly disheartening. It signaled that their commitment was neither seen nor valued, while hostile voices were allowed to expand unchallenged and unchecked.

Pic.1: On 18th Sept 2023, Ilan Pappe was invited to speak at Peking University, invited and organized by the Hebrew Department of Peking University.

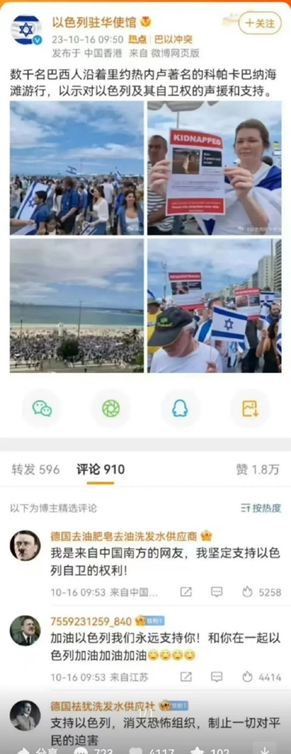

A second weakness lay in the Ambassador’s disengagement from higher education. Chinese universities have been playing a central role in shaping elite opinion, yet during Ben-Abba’s tenure, the embassy rarely attempted to cultivate ties. When a campus-wide Jewish Civilization course (see Pic. 3) – the largest of its kind in China – invited her to participate in 2021, the request was declined without discussion.

Pic. 2: WeChat correspondence reveals that the Israeli embassy rejected an invitation for the Ambassador to visit Peking University – China’s most influential academic platform – illustrating a significant missed opportunity in Israel’s public diplomacy.

After October 7, the embassy found itself without any access to the universities and scholars who shape how China understands Israel. Because no academic relationships had been built in advance, there were simply no channels through which Israel could speak to the audiences that mattered most.

Pic 3: Professor Meng Yang’s Jewish Civilization course – now the largest course on Jewish studies in China – invited the Ambassador to speak to its students, but the Israeli embassy declined the request.

A third scandal appeared in April 2022, at an event held at Peking University to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Sino-Israeli diplomatic relations. What should have been a celebratory occasion instead became a moment of embarrassment: a Chinese student attended wearing an Arab keffiyeh as a form of protest, and the event moderator was a notoriously known antisemitic influencer in Chinese social media, as reported by Israeli scholar Tuvia Gering (see Pic 5).[1]

These incidents revealed the absence of basic due diligence, i.e. no background checks, no analysis of online reputations, and no risk assessment. The scandal was astonishing for an event marking the 30th anniversary of diplomatic relations. A moment meant to symbolize thirty years of cooperation became, through the embassy’s lack of basic vetting and risk assessment, a stage for anti-Israel and antisemitic gestures.

Pic 4: A Chinese student wore a keffiyeh in protest during the 30th anniversary event of Sino–Israeli diplomatic relations, while Ambassador Ben-Abba was speaking.

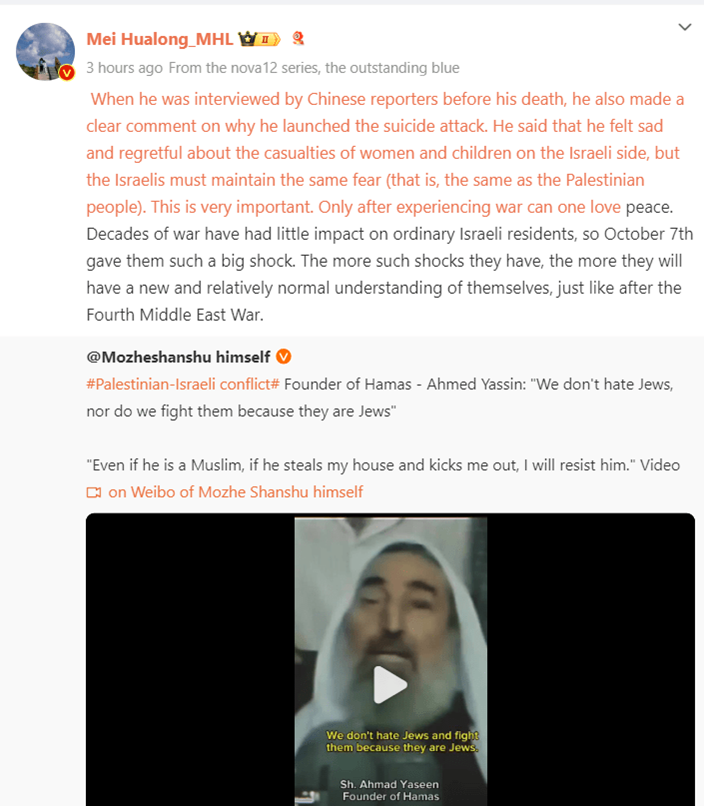

Pic 5: Moderator of the event Mei Hualong, a Harvard-educated assistant professor at Peking University in the Hebrew Department of the School of Foreign Languages, and a Research Fellow at the Institute of Israel and Jewish Studies has been spending what seems like several hours each day disseminating anti-Israeli and blatantly antisemitic content (under the guise of “anti-Zionism”) to his 1.12 million followers. All the while, Mei offers a continuous stream of apologetics for Hamas terrorists (“resistance is the only path to peace”) and attacks anyone in China who supports Israel.[2]

Fourth, the embassy only began reaching out to scholars after October 7. Several senior Chinese academics noted privately that the embassy had not contacted them in years, but turned to them urgently once the crisis began. Public diplomacy cannot be improvised; it relies on long-term cultivation, trust, and continuity. None of these were in place during her term.

Fifth, the embassy’s digital communication after October 7 generated a series of scandals. Numerous official WeChat posts by the Israeli embassy were released with unedited machine translation, resulting in awkward, inaccurate, and culturally tone-deaf messages that conveyed disrespect to Chinese readers. Even more damaging were many incidents in which WeChat posts prominently featured reader comments containing Hitler avatars. This was not a minor oversight: the issue was so glaring that any staff member with even minimal familiarity with global antisemitism should have recognized it instantly. The fact that the comment was highlighted raises legitimate questions: whether the cause was negligence, a complete breakdown in internal review, or even deliberate sabotage by locally hired staff. While intent remains unknown, the very plausibility of these interpretations is alarming.

Pic 6: On the embassy’s official WeChat account, comments containing Hitler avatars were not only left visible but were highlighted as “featured comments,” revealing a remarkable lapse in content review.

Similar issues appeared in other regional consulates in China. The Shanghai consulate’s public collaboration with the Anti-Defamation League triggered intense online backlash. The Chengdu consulate issued an error-filled public letter that went viral as a joke, further harming Israel’s wartime image. At their core, these incidents demonstrated something deeper: the consulates did not understand Chinese society at all. They did not know how Chinese publics read, react, or mobilize online. As a result, the consulates not only failed to communicate, but also generated ridicule, undermining Israel’s credibility at a critical moment.

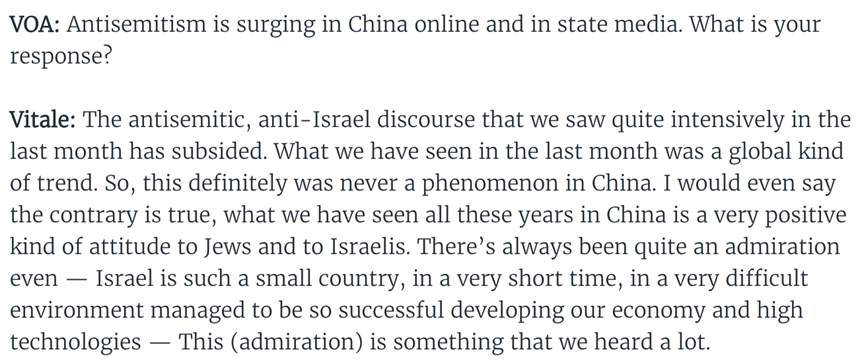

A fatal mistake emerged when Ambassador Ben-Abba mischaracterized the situation in China during a November 2023 interview with Voice of America, stating that antisemitism had “subdued.” This assessment was demonstrably inaccurate and suggested a serious disconnect between the embassy’s internal evaluations and observable reality. Her claim did real damage. It was not simply wrong; it reflected an alarming ignorance of the situation and transmitted that ignorance back to Jerusalem, shaping policy with a false picture of reality. At a time when informed judgment was essential, the embassy misled its own government. And for the few people in China who were actively fighting antisemitic and anti-Israel narratives, her remarks were devastating. Her remarks signaled that the very institution meant to support them had no grasp of the struggle they were facing.

Pic 7: transcript of the VOA interview.[3]

Her term ended early, after she publicly criticized her own government at an official event in the embassy. Her planned farewell reception was canceled.

I would put her approach as “internal criticism, external silence.” She did not meaningfully counter rising antisemitism in China, yet publicly challenged her own government near the end of her term. So is her dismissal “ironic”? Strictly speaking, no. Ambassadors who criticize their own governments are dismissed everywhere. But the real irony lies elsewhere: She remained silent where her voice was urgently needed: in confronting antisemitism in China. And she spoke only where silence was expected, in criticizing her own government. Her silence had no consequences. Her speech ended her term.

This exposes the core issue: Ambassador Ben-Abba was not the problem. She was the symptom, a symptom of a diplomatic system weakened by political appointments that substitute personal loyalty for professional expertise; a symptom of institutional failures marked by the absence of basic due-diligence procedures, effective oversight, and any meaningful preparation for the complexities of China’s rapidly shifting discourse and political environment; and a symptom of a persistent failure to treat China as a serious diplomatic arena, leading Israel to send underprepared personnel to one of its most challenging postings – a structural weakness that long predates Ambassador Ben-Abba and will outlast her unless addressed.

And perhaps the sharpest irony is this: the embassy has still not grasped the political implications of the State of Qatar Chair becoming firmly embedded at the Chinese top university Peking University (the only Qatar center in Asia) – an institutional presence that now shapes Middle Eastern discourse on campus far more actively than Israel itself. Even more troubling is the deeper paradox that the very Hebrew program Israel once supported has, over the years, come to be anchored by a Chinese scholar widely recognized as one of the most notorious purveyors of antisemitic narratives in contemporary China. What was intended to serve as a bridge of cultural understanding has instead become an incubator of hostility.

Pic 8: The State of Qatar Chair on Peking University’s website.[4]

Few developments reveal Israel’s strategic blind spots with such painful clarity. Where Israel stepped back, others advanced with purpose; where Israel assumed that goodwill would sustain itself, an entirely different narrative ecosystem consolidated – one that now shapes how a new generation of Chinese students will come to understand Jews and Israel. If Israel does not fundamentally rethink its diplomatic posture toward China, it will not merely lose influence. It will forfeit the ability to define itself, leaving the story of Israel in China to be written not by partners seeking understanding, but by actors fully prepared and strategically positioned to impose their own interpretations.

Dr. Yang Meng teaches Judaism and Yiddish studies in Peking University, China.

[1] Tuvia Gering, The Mission of the Historian, Discourse Power (Sept. 17, 2024) https://discoursepower.substack.com/p/the-mission-of-the-historian

[2] Ibid.

[3] Meng-Li Yang, Q&A: Israel’s Ambassador Says China’s Online Antisemitism Part of Global Phenomenon, VOA (Nov. 28, 2023), https://did.li/JEGOf

[4] Mission & Vision, Peking University—Qatar Chair, https://did.li/ciMx5